The third in a series of articles on arts administration.

One of the most frequent questions an arts administrator gets asked by members of the audience or interested others is, “How do you decide what’s on the program?” Or, on a very bad day, “How did that damned piece of trash get programmed?”

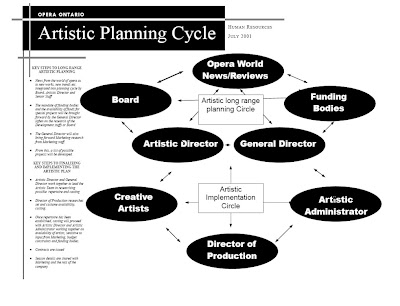

When I served as interim General Director of Opera Ontario, I played a key role in an initiative to look at the processes within the organization with a view to reforming the human resource structures that supported those processes. Here’s what the artistic planning flow chart looked like.

Whether you can read the fine print in the diagram or not, it should be clear that the answer of how program planning happens is not a simple one! This is true of all arts organizations but I am going to speak from what I know best, the planning processes in orchestra, opera and music presenting organizations.

Whether you can read the fine print in the diagram or not, it should be clear that the answer of how program planning happens is not a simple one! This is true of all arts organizations but I am going to speak from what I know best, the planning processes in orchestra, opera and music presenting organizations.

Central to the planning process is the relationship and exchange of ideas between the Artistic Director or Music Director and whomever is in the key Artistic Administrator role–in the case of the chart above the Central role in planning is the relationship between the Music Director and the General Director, with many other streams feeding information into the mix.

Sometimes audience members assume that the Artistic Director or Music Director is solely responsible for what gets on stage or is heard in the concert hall. While the AD has a key role in setting the priorities for the season, usually decides on the theme for artistic seasons and the repertoire for many concerts, it is rare to find a situation in which the AD takes total responsibility for artistic planning. Why?

Time is one obvious factor. In a major US orchestra where I served as Artistic Coordinator, the Music Director spent 14 weeks with us during the year, half of that time was spent in rehearsal, leaving little time for Artistic Planning meetings. Many Music Directors lead more than one orchestra and have active guest conducting lives. Our orchestra performed 150 concerts during a 39 week season. It’s not hard to see that others would have to connect the dots in the Music Director’s plan for the season. The Music Director would set out the plan for major concerts, plan the repertoire, indicate some guest artists, shortlist alternatives and leave it to us to try to make happen. We’d touch base over the roughly three years that it takes from initial plan to season announcement, tweaking repertoire, artist line-up and schedule.

In addition to the input from the Artistic Director, arts organizations have to listen to their audience, consider what their budget can manage, keep on top of trends in the arts community, listen to the needs and abilities of their musicians, consider priorities of government arts councils, and consider other funding sources for programming. Secondarily, arts organizations have to consider links to other programming, ties to festivals and/or community events, and finally, the logistics of production planning.

I frequently hear from audience members who wonder–sometimes with considerable irritation and longing–why we “just can’t program the music that everyone knows and loves.” And there are several answers.

The first one is that audience taste IS a huge part of what we think about when we program–but it can’t be the only thing. Experience has taught arts administrators that even the audience tires of programming that only offers them mainstream repertoire. The fact is that people don’t know what they like until you offer it to them. The sucessful Artistic Director will offer their audience the occasional unfamiliar fare that will fit well with more familiar programming to tweak their interest and give them something novel to think about. Only then does the programming stay fresh.

We pay our Artistic Director for his/her vision as an artist and we have to respect that vision and not subjugate it unduly to audience taste. But obviously we can’t pay our Artistic Director if no one comes to the concerts so those two polarities are really an important balancing act in programming. But they are not the only forces.

In thinking about the development of our musicians, we have to provide them with some new challenges to keep their artistic lives interesting and to retain the best musicians–a goal that also serves our audiences well.

We also have to consider the mandate of our national, provincial and municipal Arts Councils in developing and supporting artists and the body of creative art within their jurisdiction. More than once I have heard Board Members in meetings–sometimes with Arts Councils–say, “but you are penalizing us for programming what is popular, what the audience wants”.

Yes they are, …. and …. what’s more…in some ways, that’s their job.

This is astonishing news to rookie Board Members who often believe that the job of Arts Councils is to reward the number of bodies you put in seats at your concerts. Quite the contrary. The Arts Councils’ job is support the development of art with a longer view–to support that which is not commercially viable, or not yet commercially viable, and in particular to foster the artists and creative arts within their jurisdiction.

So if your organization relies on funding from government arts councils–and in Canada music organizations derive an average of 30% of their annual budget from government sources according to the last survey of the Business and the Arts Council–then you have to consider in what way your programming can utilize local artists and music composed within our own country, province and municipality. For those of us that care about the future of the art form, this is not an onerous task, but really makes us a living part of the art form as opposed to serving in the other important role of being curators of the art of the past. Where would Mozart have been if the audiences of his day turned up their noses at “new music” and refused to listen to what were then contemporary compositions?

Participating in community festivals can provide several huge bonuses to arts organizations and this participation generally impacts on programming. (eg. In order to qualify for a regional Mozart festival, you generally have to program Mozart.)

Sometimes the reverse happens and programming can suggest festival possibilities. As General Manager of Soundstreams Canada in 2003-2004, we were programming a major concert of works by R. Murray Schafer on the occasion of his 70th birthday year. It seemed likely that others would be doing the same and so we looked about and asked those organizations to join us in packaging and marketing our various concerts as a Schafer festival.

The advantages to this sort of festival are: the ability to pool marketing dollars and get more marketing than any one arts organization could afford, cross-marketing between the audiences of each arts organization, the access to special funds ear-marked for festivals, sharing resources of various kinds between arts organizations, package deals that benefit arts attenders, the ability to build comprehensive arts education events around the thematically linked events. Programming for existing festivals or to make festivals possible is a win-win for everyone.

Less obvious to the audience members may be the links that the arts organization is making to educational or audience o

utreach initiatives. For example, the audience members at an orchestra series may not know that the programming of three works relating to literature over three concerts, is part of a “Literacy in Education” project that is being delivered in community High Schools. Programming those works not only builds cross-curricular connections for students but also allows for some economies for the orchestra in being able to apply some of the educational program funding to administrative costs and rehearsal costs, as allowed by the program. Building an educational program or educational concert on repertoire being offered on a main stage concert makes that program more affordable.

Audience outreach programs both deepen the enjoyment and understanding of existing audience and are initiatives that reach out to potential new audience members. For an example this season, my orchestra, the Toronto Philharmonia, is doing some outreach to the Chinese community that lives within the audience catchment area. We have programmed this concert which features a composition for erhu and orchestra and Chinese classical music artists, in the hopes of engaging newer members of our community and attracting the investment of Chinese business and corporations in the area. But we wouldn’t have programmed it unless our Artistic Director thought it was great music and fit well in the context of this season. We also hope our existing audience will find the program engaging, broadening their experience to the sounds of a Chinese traditional instrument–albeit in the context of a western orchestra concerto.

The importance of programming within budget is largely self-explanatory but the way this plays out within the program planning team may not be so clear. We start with a draft budget of assumptions about artistic costs. When one concert is finalized over-budget because the soloists could not be contracted for less or the Music Director insists on a larger orchestra, we have to make up the savings on another concert. This can involve decisions ranging from presenting an emerging artist, a concert with a chamber-sized orchestra or deciding that the concert must be programmed entirely from music that the orchestra owns–to save on music rental and shipping costs.

Of particular interest to artists is how those rare “emerging artists” spots are filled. It is simpler to tell you how they don’t get filled. In my experience it is never because an agent has talked us into it or an unsolicited CD arriving on our desk has blown us away. Agent material and unsolicited CD’s are disposed of unopened in most arts organizations–a terrible waste but no one has the time or inclination to review them and returning the material costs us money. Most often the Music Director has heard the young artist perform with another orchestra, a recital or at a competition, and extends an invitation to the young performer to appear with the orchestra in a future season. Occasionally the recommendation can come from another trusted source. Sometimes organizations tap into young artist programs from Europe or Asia that subsidize travel or otherwise help with the programming of young artists from their country. Lastly, we may choose to develop and promote the careers our own musicians by offering them a concerto appearance. This year our orchestra is presenting our Principal Violist, Jonathan Craig, playing the lovely Walton Viola Concerto on April 10 2008. details.

When people ask me about how financial considerations affect programming, they are often asking whether corporations, major donors, foundations or government arts councils force particular programming choices on the orchestra. I have to say that I have never known that to happen–which surprises people. What happens more often is that we have two or three artistic ideas and only one of them finds sponsorship. We look at the mandate and interests of a corporate or foundation funder and pitch them the program that we think might appeal.

How does production logistics affect programming? Usually a program starts with one artist or repertoire selection that is non-negotiable and all else is built around that core.

If we have X artist playing Y concerto, we first consider the instrumentation of the chosen Y concerto. If it has, for example, harp and trombones as part of the orchestration, we’ll want to utilize them in the other half of the program–or at least we’ll have that option. If the concerto has a smaller orchestra with limited brass, no harp, no piano, we may want to look at a complimentary programming selection within the instrumentation of our core selection. Otherwise we are adding cost to our program–perhaps to little artistic value.

What else? We consider the problem of seating latecomers in building our program–the main reason why so many concerts begin with short works– and we have to also think about our concert order.

I overheard a group of audience members speculating recently about why the symphony was on the first half and the concerto was on the second half–a less frequent concert order. Speculation ranged from, “they wanted to stop people from going home at the intermission who just came for the soloist”, through, “that symphony would have put me to sleep in the second half”, to “they wanted to end with a bang!”

All excellent thoughts and worthy of consideration. However, the real reason was that the opening small work at the top of the concert had orchestral piano as a part of the instrumentation. Had we also had the piano concerto in the first half, we would have been required to move all of the violins off stage, move most of the violin section’s chairs and music stands, then move the piano from the rear of the orchestra into soloist position–all while the audience sat twiddling their thumbs and rattling their programs. A tasteless interruption in a beautiful evening of music.

These are just some of the factors that must be balanced in programming an arts season. And finally, despite the varied considerations and forces acting on programming, the season must emerge with a sense of unified artistic vision through the Music Director’s ability to say “no” to whatever great or cost-saving idea might come forward when it really is just not artistically possible.

No comment yet, add your voice below!